How stress affects our memory

Yikes, you pass someone down the street and you cannot remember their name? You go through every part of the brain trying to remember the where, how and circumstance that you know them but it just does not connect. Better still you’re thinking of that film with the car crash and the leading lady has been in several blockbuster films plus some TV serials. You can picture her face, her lips, her accent, her long flowing hair, but you still can’t remember her name – hell no. You’re in a final exam or doing your driving test and a question comes up, you know it’s on the tip of your tongue but you are breaking out in a sweat trying to guess the answer. You’re at a social engagement, like meeting the in laws, and you have a game of charades after in which you can’t remember a thing and look stupid.

Could your stressors be affecting your memory?

Short term stress enhances the memory and cognition, while major or long term stressors are disruptive. In order to understand and appreciate stress and how memory is consolidated, retrieved and how they can fail. Memory is both short term and long term. Short term memory is your brain’s equivalent of juggling some balls in the air for 30 seconds. In contrast long term memory refers to remembering what you had for dinner last night or your school name. Neuropsychologists are coming to recognise that there is a special subset of long term memory. Remote memories are the ones stretching back to your childhood village, your native language, the smell of your grandmothers baking . Often patients who have dementia that devastate the short term memory, retain many long term remote facets.

Memories are transferred between what’s called explicit (declarative) and implicit (which includes an important sub-type called procedural memory). Explicit memory is based on facts and events like it’s Tuesday, and I have pilates today, my teacher has blonde hair and short nails. Implicit is remembering skills and habits on how to do things like the short spine pilates exercise with breath or the sun salutations, remembering the precise breath pattern the inhale and exhale in both sequences.

Each time your movement sequence approaches you subconsciously remember what to do like shifting gears in a car. One day in class while moving you will sail through a movement pattern without having to think about it. You did this implicitly rather than explicitly.

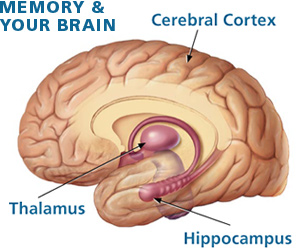

There are different areas of the brain that are involved in storage and memory and retrieval. One site is the cortex, called the hippocampus (that’s Latin for sea horse) which the hippocampus vaguely resembles if you’ve been stuck inside a neuro anatomy book for too long instead of going on the seashore.

Both of these are regions vital for to memory – for example it’s the hippocampus and cortex that are damaged in Alzheimers disease. A totally simplistic view would be thinking of the cortex as a computer hard drive, where memories are stored and your hippocampus as the keyboard where you place and access memory through the cortex.

So how is movement and memory connected? Well there are different brain regions that appear to be connected to implicit procedural memory, the type you need to perform reflexive , motor actions, without even consciously thinking about them.

So what is the relation to stress and memory – whats going on within the clusters of of neurons within the hippocampus and cortex? Rather than memory and information being stored in single neurons, they are stored in networks of hundreds connections. Neuroscientists have come to think of both learning and storing of memories as involving strengthening of some branches. The strengthening occurs between the tiny gaps called synapses. When a neuron has heard some fabulous gossip and wants to pass it on, a wave of electrical excitation sweeps over it, that triggers the release of chemical messengers- neurotransmitters- that float across the synapse and excite the next neuron. There are dozens, probably hundreds of different kinds of transmitters and synapses in the hippocampus and cortex,.

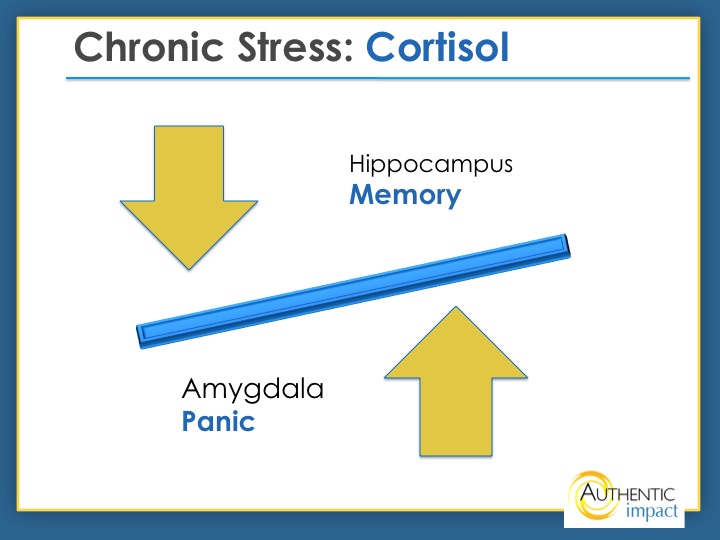

When we are stressed our sympathetic nervous system kicks in pouring epinephrine, norepinephrine into the bloodstream. This keeps us alert by arousing the hippocampus facilitating memory consolidation. This area of the brain gives us a central understanding of anxiety (amygdala). It has a second route for enhancing cognition. Tons of energy are needed for all that explosive , non linear, long term potentiating, the turning on of light bulbs in your hippocampus and glutamate. The sympathetic nervous system helps those energy needs to be met by mobilising glucose into the bloodstream and increasing the force with which blood is being pumped into the brain.

So stress acutely causes increase delivery of glucose to the brain, making more energy in the neurons and therefore better formation and retrieval. The mild elevation in glucocorticoid is the type you would see during a moderate short term stressor. This occurs in the hippocampus where those moderately short term stressors make us more sensitive. Our taste buds, olfactory receptors, the cochlear cells in your ears require less stimulation to get excited under moderate stress and pass the information onto the brain. In that special few seconds you can hear a coke can being opened hundreds of yards away.

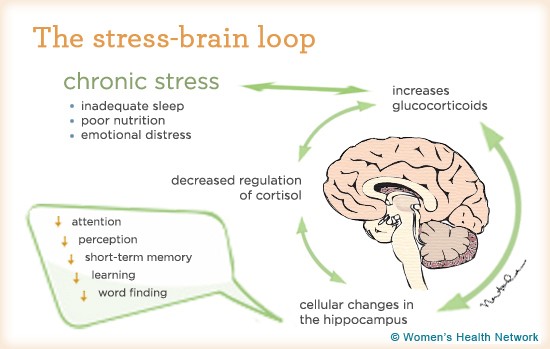

When stress goes on for too long results in memory loss. This has been shown in many studies when extra glucocorticoids are added to the subject totally messing up their brains. The results are poor muscle co-ordination or responsive to sensory information.

A sever case in humans is ‘Cushings syndrome’ – the symptoms are high blood pressure, diabetes , immune suppression, reproductive problems, the works. The memory loss s known as cushingoid dementia. With prolonged treatment , explicit memory problems develop. Pamela Keenan of Wayne State University has studied individuals with these inflammatory diseases, comparing those treated with steroidal compounds and those getting non steroidal , memory problems were a problem of those getting the glucorticiods , not the disease.

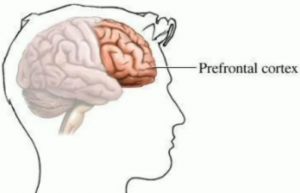

There is also evidence that stress effects our “executive function’. That is to say that this is different from memory being the cognitive realm of storing and retrieving facts, this concerns with what you do with the facts, whether you organise them strategically how they guide your judgements and decision making . This is the provence part of processes brain called prefrontal cortex.

When stress effects the hippocampus , the hypercampal neurons don’t work as well. Once glucocorticoids levels go from moderate to big time stress, the connection between the two neurons that should become excitable by pass the the hormone that that no longer enhances long term pronation. High glucocorticoids enhance long term depression, which may be a forgetting mechanism.

We know from earlier an excess of stress or glucocorticoids can disrupt functioning of the hippocampus. There are six sets of finings that disconnect neural networks by atrophying of processes, inhibit the birth of new neurons, worsen the neuron death caused by neurological insults, or overly kill neurons.

The six findings are :

- Cushings syndrome involves any number of tumours that produce avast damaging excess of glucocorticoids – were the consequences include impairment of the hippocampal – dependent memory.

- Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) shows that people with repeated trauma rather than a single trauma have smaller hippocampus. This would be seen in children that have been repeatedly abused or soldiers.

- Major depression is intertwined with prolonged stress, and this connection includes elevated glucocorticoid levels in about half the people with major depression. The more prolonged the history of depression, the more volume loss. Furthermore its in patients with a sub type of depression that is most associated with elevated glucocorticoid levels where there is a smaller hippocampus

- Repeated jet lag – the shorter amount of time to recover from fights the smaller the hippocampus and yet more memory problems

- The ageing process- as we age there is a rise in our resting glucorticoid levels plus the size of our hipoocamos.

- Interactions between glucocorticoids and neurological insults. A handful of studies report that the same severity of a stroke, the higher the glucocorticoid levels in a person

About 16 million prescriptions are written annually in the united states for glucocorticoids . Much of the use is benign- a little hydrocortisone cream for someone with poison ivy, a hydrocortisone injection for a knee, hip of facet joint, a steroid inhaler for asthma (which is the most worrisome route for glucocticolids to suppress the inappropriate immune response in autoimmune diseases(such as lupus, multiple sclerosis or rheumatoid arthritis). So as discussed earlier prolonged glucortociod exposure in these individuals is associated with problems with hipoocampal dependent memory. So should you avoid taking glucocorticoid for your auto immune disease? Perhaps not as there are devastating diseases that use glucocorticoid as a treatment that are highly effective however the side effects are with memory loss are grim.

Bibliography

“Why do zebras get ulcers” – Robert .M. Salsposky